Folsom Street Fair: The Early Years

First, it’s important to understand why South of Market, or SoMa, is considered the leather district in San Francisco. From the 1960s to the early 1980s, more than 30 gay leather bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs thrived in the area, nicknamed the Folsom “Miracle Mile”. It was, by many accounts, a horny gay paradise, particularly for those gay men who didn’t feel the effeminate stereotype of homosexuality fit them. San Francisco’s SoMa offered another possibility, one which got national attention in 1964, when Life magazine published an article about homosexuality in America. Alongside the article was a photo featuring a mural on the side of the Tool Box, San Francisco’s first leather bar in the SoMa neighborhood. The mural, by local artist Chuck Arnett, was a black and white image of men in black jackets with chiseled jawlines. It was a siren call to gay men across the United States, who saw themselves reflected, many of the first time. While the Castro was the hotspot for gay politics, it was SoMa that was its throbbing libido.

Due to all that, it may surprise you to know that the first Folsom Street Fair was more of an anti-gentrification effort than it was a leather event. Called “Megahood,” it was organized by Kathleen Connell and Michael Valerio, two gay neighborhood activists who were generally more focused on fighting City Hall’s attempts to crack down on SoMa’s leather community in order to gentrify it. Valerio and Connell came together initially as part of the South of Market Alliance, speaking on behalf of affordable housing and community-driven economic development, instead of flooding the neighborhood with high-rise towers. The two realized that what they needed to bring the gay community together to protect SoMa was something that would unite pleasure and politics, much like local politician Harvey Milk had done with the Castro Street Fair.

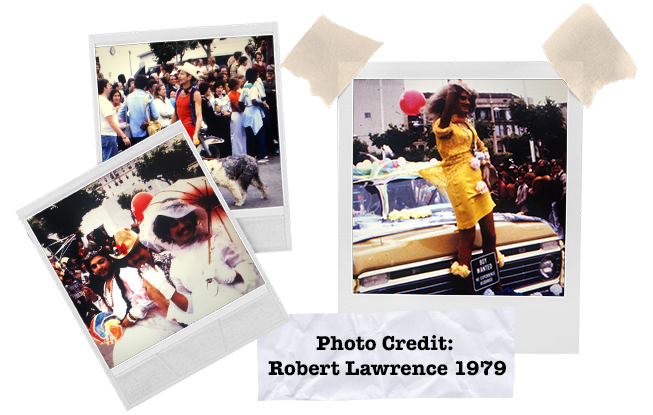

And so, in 1984, Megahood was born. It looked very different from Folsom Street Fair today – in fact, only 3 leather-aligned organizations were present, with local artists selling their wares, musicians playing for the crowds, and 200 classic cars on display. The goal was to show that the Folsom area was not a blighted, abandoned neighborhood in need of revitalization, but rather an already vibrant and diverse community of people. It was an immediate success, raising money for charity, and for the first few years, it would double in size, then double in size again as word got out.

But while this was going on, so was the slow onslaught of AIDS, leaving devastation in its wake. The leather community was fundraising in every way they could to help support the AIDS Emergency Fund, Project Open Hand, AIDS hospices, and other community responses. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people, mostly gay men, were dying of AIDS, while states debated whether or not to quarantine and isolate them from the rest of the community. SF politicians casually discussed how it would impact local politics if this “gay cancer” wiped all the homosexuals from the map. Citing public health concerns, gay bars and bathhouses were being shuttered by local governments. It seemed like all the political power that LGBTQ+ folks had managed to fight for was at risk of disappearing when it was most needed